Papaver Somniferum

Opium poppy

My Latin name is Papaver somniferum. The derivation of my name is not altogether clear; the word ‘papaver’ may have come from ‘pap’, meaning ‘bloated’, referring to my swollen fruit.

It may also be derived from the Celtic word ‘papa’, meaning porridge. In the past, the sap of my fruit was used to make a porridge that would soothe crying infants.

‘Somniferum’ links two Latin words, ‘somni’ (sleep) and ‘fer’ (to bring), so it literally means ‘bringer of sleep’: what we would today call a soporific. This has to do with my milky sap, which does, indeed, induce sleep.

In Dutch I am also called ‘slaapbol’, the word ‘bol’ referring to the hard, round seed capsule that forms after the poppy has bloomed.

In English they call me ‘opium poppy’ or ‘breadseed poppy’ and in French ‘pavot à opium’, because I am a member of the poppy family from which opium can be extracted.

Pain is an unpleasant sensation, so we should not be surprised that humans have always searched for ways to alleviate it.

As long ago as the Stone Age, extracts from leaves of the henbane plant were used to dull pain.

The Ancient Greeks used me, the opium poppy. They cultivated me to harvest oil from my seeds, which have mildly sedative effects.

Later on they also discovered the white latex sap that drips out if the unripe seed capsule is cut, and which has a much stronger sedative effect.

They used it to treat asthma, stomach illnesses, and poor eyesight.

For a long time it was unclear what part of my milky sap had these effects. It was 1805 before the active ingredient was successfully isolated, by the German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner.

He called it ‘morphium’, after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams.

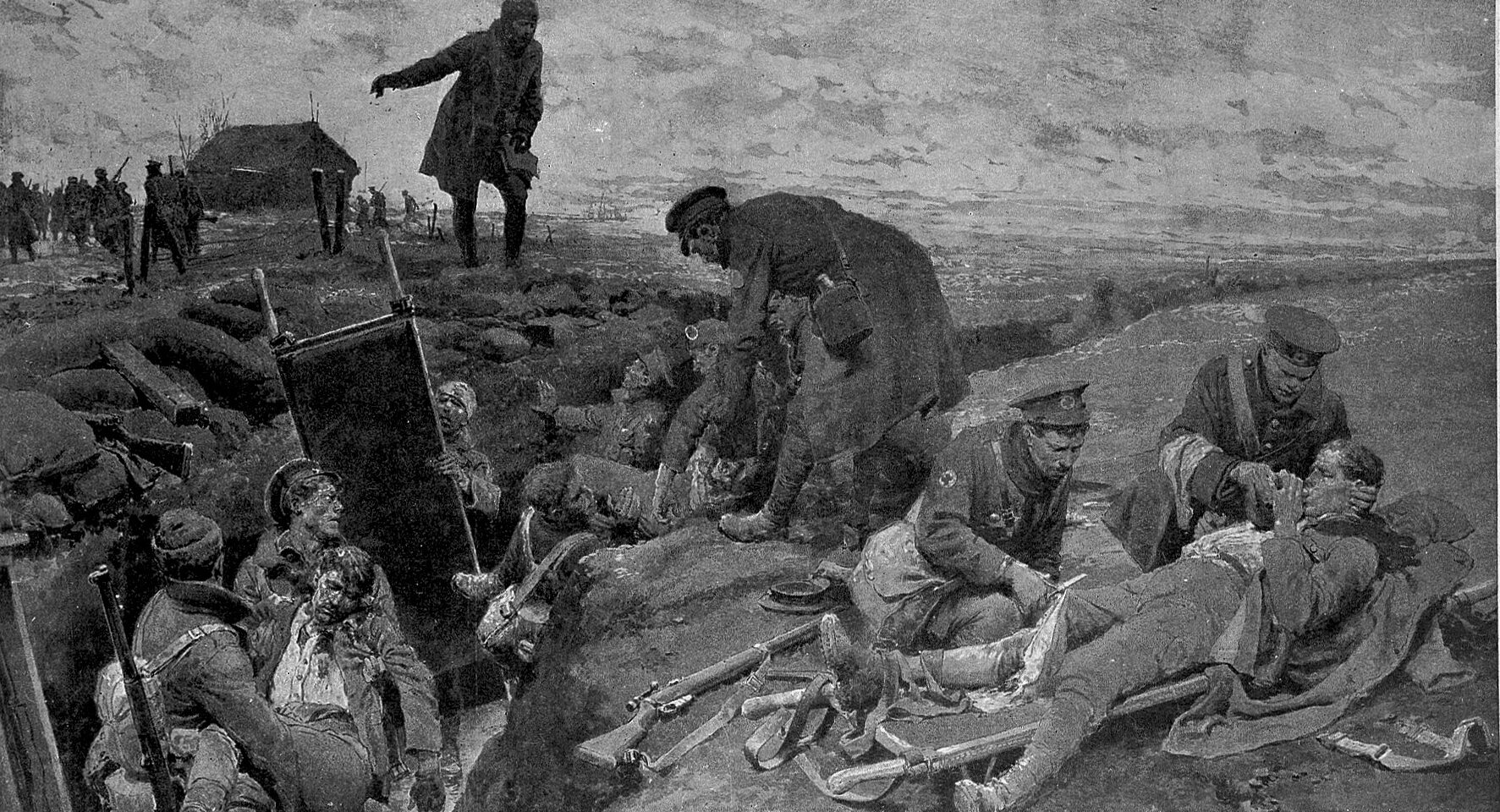

Morphine turned out to be an excellent painkiller. During the First World War it was used on a huge scale to help wounded men sleep – or to let them die peacefully.

The soldier and physician John McCrae was probably referring to this in his well-known poem ‘In Flanders Fields’ (1915) when he wrote the words: “We shall not sleep, though poppies grow in Flanders fields”.

The poppies McCrae saw were probably not opium poppies,

however the association with the opium he was constantly administering is understandable.

Today, Britons wear a poppy every year on Remembrance Day to commemorate those who died in World War I.

Morphine is still used today to alleviate severe pain, for instance after an operation or a heart attack – or to relieve pain and suffering in people who are not going to get better.

The Ancient Greeks knew it: my dried sap not only relieves pain – it also causes a most pleasant sensation.

They were very fond of using the sap (that they called ‘opion’, juice, which we turned into ‘opium’) for their parties.

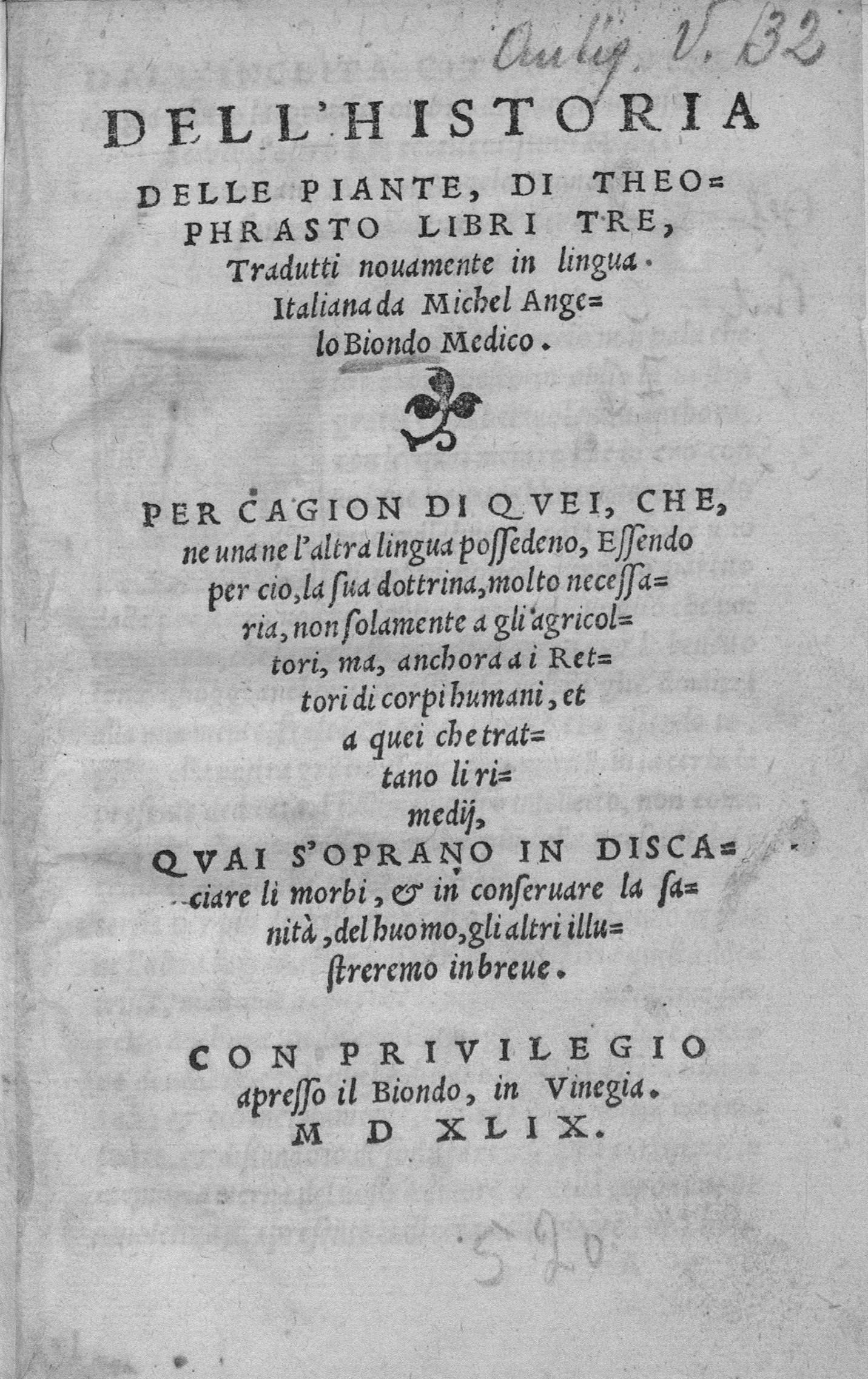

And they certainly knew it was a potent substance. In his ‘Historia Plantarum’ the physician Theophrastus says:

“Use a handful for euphoria, twice that for delusions, three times as much to become permanently insane, and four times this amount if death must follow.”

In the 17th century opium reached China, where under the influence of the Dutch East India Company it became both a malarial medicine and an intoxicant.

The Chinese became addicted to the drug, and the colonists, naturally, exploited this craving.

Around 1790 the Company was exporting about 300 tons of opium to China every year, which eventually led to two full-scale ‘opium wars’.

Still, opium is by no means as strong as the drug created by a English chemist who used opium as its raw material: heroin.

Heroin was first produced in 1874, and was given the name because it was meant to win the battle against terrible diseases – such as morphine addiction.

It affects dopamine and pain transmission in the brain, so the user feels peaceful and relaxed and feels no pain.

Alas, it quickly became clear that heroin was very, very addictive. It has been banned as a hard drug in most countries, and not for nothing.

In places like Afghanistan I am still cultivated on a huge scale for the heroin market. There you can find hundreds of thousands of poppy fields full of pink and white poppy flowers.

They look beautiful, but they are forbidden. The poppy fields also bring misery: many are in the hands of large terrorist organisations, and the fight against these groups is costing ever more lives.

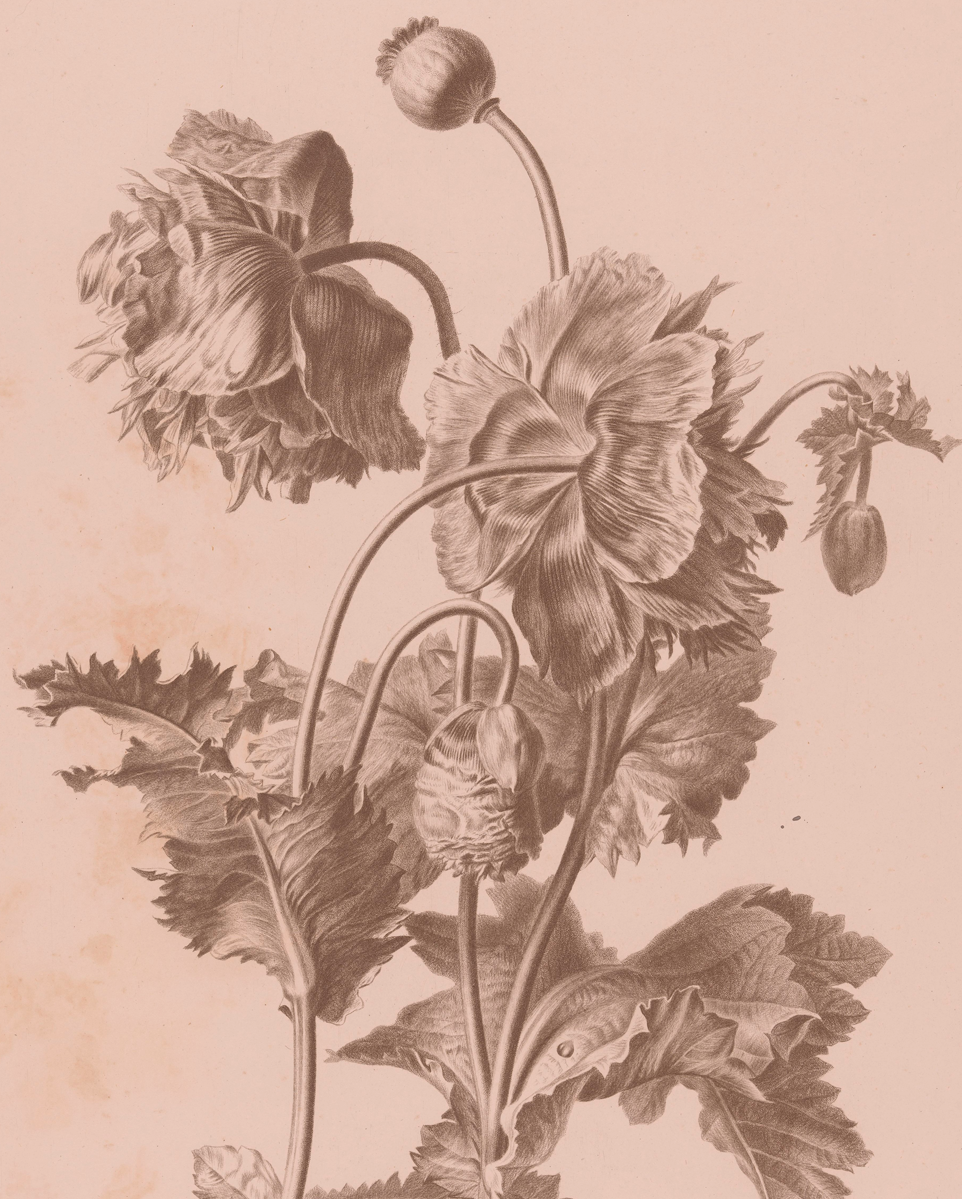

I was not painted very much in 17th-century Dutch still lives of flowers, because I had not been seen very often in the Netherlands at that time.

It was only at the end of the century that the Dutch East India Company took me home with them from the Balkans. Still, I can be seen in a few still lives.

There’s a red and white poppy in ‘Vase of Flowers’ (1660) by Jan Davidsz. De Heem, for instance,

and a bright red one in Maria Oosterwyck’s ‘Bloemen in een versierde vaas’.

I also appear in ‘Vase with flowers’ (1700), a still life by Rachel Ruysch, one of the very few female master painters in the Netherlands, and the daughter of the famous Amsterdam professor of anatomy and botany Frederik Ruysch.

The painting shows a bouquet that’s past its best: the flowers are drooping and starting to fade.

A flower has been cut off at the centre of the bouquet, leaving a clear gap. And it must have just happened, because the stalk is still dripping sap.

The drops are falling onto large poppy leaves and slowly rolling down. It seems very likely that I, the large red opium poppy, famous for my brief bloom, am the flower that was cut out.

A few years ago dozens of restaurants in China were caught seasoning their dishes with ground poppy.

The cooks were mixing the powder, containing low doses of opiates – codeine and morphine – into their soups and seafood dishes.

But why? They hoped that their customers would keep coming back for the ‘addictive’ taste. Whether that actually happened, or whether it’s even possible to get people addicted to such small amounts, is still unclear.

Incidentally, you too probably sometimes eat opiates without knowing. Dried poppy seeds also contain traces of the same substances found in opioids.

The Dutch call those seeds ‘maanzaad’, moonseed. And a couple of tasty moon-seed buns can even result in testing positive for drugs. But don’t panic: if you wanted to get high on moonseed, you’d have to eat several kilos of it.

Hi, my name is Opium poppy. Do you want to know where my name comes from?

ELSPETH DIEDERIX

PAPAVER SOMNIFERUM (BOLPAPAVER)

Opium poppy

name

Papaver somniferum

Height

80-100 cm

Flowering time

June-September

Family

Papaveraceae

name

Papaver somniferum

Height

80-100 cm

Flowering time

June-September

Family

Papaveraceae